I recently watched The Diplomat (Netflix’s 8-episode show with Keri Russell cast as the lead, the new US Ambassador to the UK Kate Wyler, not the British TV show with the same name released 2 weeks prior) and the show was entertaining enough but I didn’t really feel any way about it until people kept sending me really angry reviews of it. The Discourse around The Diplomat is primarily driven by foreign policy nerds (a term of endearment from a fellow wonk) who primarily take issue with the liberties the show takes with the details of ambassadorial duties and international politics.

Kate’s CV is a major focus in reviews of The Diplomat. The Financial Times says that Kate has no ambassadorial experience whatsoever, making it totally absurd that she would be fit for the position of ambassador. A slew of American outlets wield the fact that Kate does have diplomatic experience as a gotcha. In an article brimming with “well actually” vibes, a Slate reporter says, “American ambassadors to St. James’ Court are never professional Foreign Service officers; the post, to a greater extent than all other postings, is reserved for prominent pols—campaign donors, party chairmen, ex-cabinet secretaries.” Twitter users say the show is unwatchable because Kate is plucked from an ambassadorship to Afghanistan to run the embassy in the UK without a Senate confirmation hearing. While there’s probably enough dramatic intrigue baked into these hearings to make a season of TV, and there’s certainly enough content for a Veep-style show about the absurdity of appointed ambassadors, that’s just…not what the show is about.

And maybe the detail of a Senate hearing can be forgiven, but for other reviewers, the show’s ignorance of geopolitical nuance cannot. These reviews take issue with the premise of the crisis driving the plot. (tl;dw[atch] – someone bombs a British aircraft carrier; everyone immediately thinks it’s Iran; Kate Wyler says, “Hmmm why would the Iranians do this?” and digs deeper; hypothesis 1 is that it’s the Russians; this is fine-tuned as hypothesis 1.1 that it’s a Wagner Group-esque group of Russian mercenaries.) Slate’s reporter doesn’t buy that Russia would frame Iran for anything (A+ for him, because characters have this same conversation on screen) and seems personally offended that showrunners didn’t take his suggestion that China makes way more sense as the baddie in this scenario. Vulture’s review contends that the geopolitical crisis makes sense, insofar as it’s predictably xenophobic toward Iran. “It’s drowning the canvas in decades of the same axis-of-evil talking points,” the author writes.

Certainly the entertainment industry’s role in the War on Terror is a disturbing history, and it is worth critical examination of tropes of The Other in popular TV and movies. But the angle of whether plots “make sense” given international actors’ prior behavior misses out on what can be gained from interpreting pop culture. “We might be tempted to analyse popular cultural representations primarily for their ‘truth value’ (historical accuracy) – i.e., what a film from a particular period can tell us about that era, or making judgements about whether individual films present a ‘balanced’ (‘true’) or ‘biased’ (‘propaganda’) view of the world,” Christina Rowley writes in Popular Culture and the Politics of the Visual. “However, representations should not be viewed as simple reflections of either ‘true’ or ‘distorted’ ‘reality’.”

Shows like Star Trek or Game of Thrones warp structural features of our world in ways that let us glean something about the nature of politics. Daniel Furman and Paul Musgrave make this point in their article “Synthetic Experiences: How Popular Culture Matters for Images of International Relations:” “Audiences watching Star Trek could discard the fictional chaff (starships, Klingons, and warp drive) from the relevant wheat (benevolent liberal hegemony leads to perpetual peace) and easily apply arguments encoded in the text to the real world (support liberal containment policy, not aggressive anti-Communist rollback).” International relations scholars who have published dozens of serious empirical and theoretical articles have also written about Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, and depictions of zombie apocalypse. So why can’t The Diplomat, another work of fiction, get a similar read?

It’s admittedly harder to break out of this “real”/”fake” binary with a show like The Diplomat than shows that sit soundly in the genres of fantasy and science fiction. The contours of the world where Kate Wyler is the US ambassador to the UK are too similar to our own to be able to suspend belief. After all, just like our world, there are NATO powers trying to figure out who’s responsible for an attack on a member country, there’s a Wagner-lookalike mercenary group, Iran is a rogue state. But… the diplomats are too hot to be real, Kate didn’t get a confirmation hearing, and her position in London isn’t for career diplomats anyway. With these gaffes, what could The Diplomat possibly tell us about politics?

To answer that, we have to wade through domestic television that blurs the line between fiction and mirror of party politics. The Diplomat was created by Debora Cahn, who was a writer-producer on The West Wing, a show that is (in)famous for its rosy vision of high politics. A reviewer for Slate sneers that The Diplomat “indulges in the same liberal-intellectual fantasy” as Cahn’s previous work. “Wouldn’t it be great if a political leader got the job just because he (or better yet, she) was good at it?” With echoes of the 2016 election, we’re supposed to credit sexism as the reason we can’t have competent leaders. This is the tone of Rolling Stone’s review, which argues that “the show’s chief concern outside its plot is the uneven playing field between men and women who do the same job.”

This is the wrong read of the show’s thesis, though. Kate has to navigate “wariness” and “skepticism” from her British counterpart and the deputy who’s been tasked with vetting her for VP. But her deputy doesn’t doubt her because she’s a woman (to the contrary, it’s made explicit that her gender is the main thing going for her potential pick as VP besides her commitment to public service over politics), he’s still reeling from Hillary’s loss in 2016 and doesn’t know if he has it in him to groom a candidate – especially one like Kate who doesn’t want the job. The British Foreign Minister isn’t guarded because she’s a woman (unless you count his withdrawal after making his crush on Kate clear), but because the U.S. has a history of giving a big middle finger to its enemies and closest allies alike.

The last 20 years of television, during which we’ve moved away from The West Wing’s picture-perfect vision of liberal president Jed Bartlet and toward complex lead characters who we root for even though they are terrible people, guide us toward a different gender story. Per Vulture’s review, Kate’s greatest crime is being a girlboss. “She’s not a regular ambassador,” the review says, but “a cool, savvy political operator who really deserves the gig (because of a bunch of unexplained stuff she did in the Middle East).” But she’s not cool, not really, and I don’t think we’re supposed to actually like Kate Wyler. She is crass (hip, breaking gender stereotypes) and stinky (gross, breaking gender stereotypes), makes a fuss about having to wear dresses (girlboss feminist) but doesn’t know that Gloria Steinem is still alive (bad feminist). Some read into Kate’s boorishness as a quality we’re supposed to like, but on the whole, she’s not a super likable character – which is fine. She doesn’t need to be particularly likable for the show’s message to come through.

And that’s because Kate isn’t the mouthpiece for the show’s thesis. That job is for Hal, Kate’s charismatic diplomat husband, who the audience can tell is an asshole because he is a sexy smooth talker who steals the spotlight. Kate asks Hal to give a speech in her stead and does a classic feint, opening his speech on the theme “communication is key” by saying “Communication isn’t the key.” For Hal, “Diplomacy never works. Until it does.” To get there though, one needs to “talk to everyone. Talk to the dictator and the war criminal. Talk to the poor schmuck three levels down who’s so pissed he has to sit in the back of the second car, he may be ready to turn. Talk to terrorists. Talk to everyone.”

It’s a little obnoxious that the thesis is laid out so explicitly in a speech, though Cahn’s oeuvre has consistently resisted the adage “show don’t tell” with character’s conversations about the importance of democratic values. But Cahn doesn’t just tell through Hal, she also tries to show through Kate.

The Diplomat shows that politicians of the Western world do all kinds of shady shit. They do this for instrumental reasons (to maintain geopolitical alliances, a theoretically justifiable cause that viewers are supposed to get the ick for; to preserve their hold on elected office, a deplorable cause that leaders from respectable allied countries aren’t supposed to do) and for spectacle (bomb Iran because we can).

And it’s Kate, a dogged public servant, who we see break procedural and diplomatic formalities to resist this. She works to speak to people who are morally reprehensible because they come from countries that have been deemed morally reprehensible. In doing so, she takes them seriously as political agents. In line with Hal’s speech, Kate challenges the truism of foreign policy that talking to an enemy legitimizes them. This notion stems from the bipolar world of US-Soviet conflict and matured during the era of American order. But this attitude isn’t fit for a multipolar world – which international relations theorists have deemed the most chaotic, the most ripe for violence.

If you want to be entertained by real geopolitical intrigue that showcases a strong, smart, capable female diplomat navigating an international crisis, make noise for a documentary on the new ambassador to Ukraine, Bridget Brink. If you want insight on how average people make sense of geopolitics (the show’s first week got more than 55 million streaming hours, averaging out to about 6.9 million views per episode) with the added bonus of watching Keri Russell look smart in a pantsuit, take off your policy wonk hat and enjoy the show.

Our driver Jomart met us at Sheron Homestay in the morning, and we stocked up 5-liter containers of water at the bazaar and pulled out money from Orion Bank. (There’s nowhere else to pull out or exchange money until well after you cross into Kyrgyzstan, so calculate what you need beforehand.)

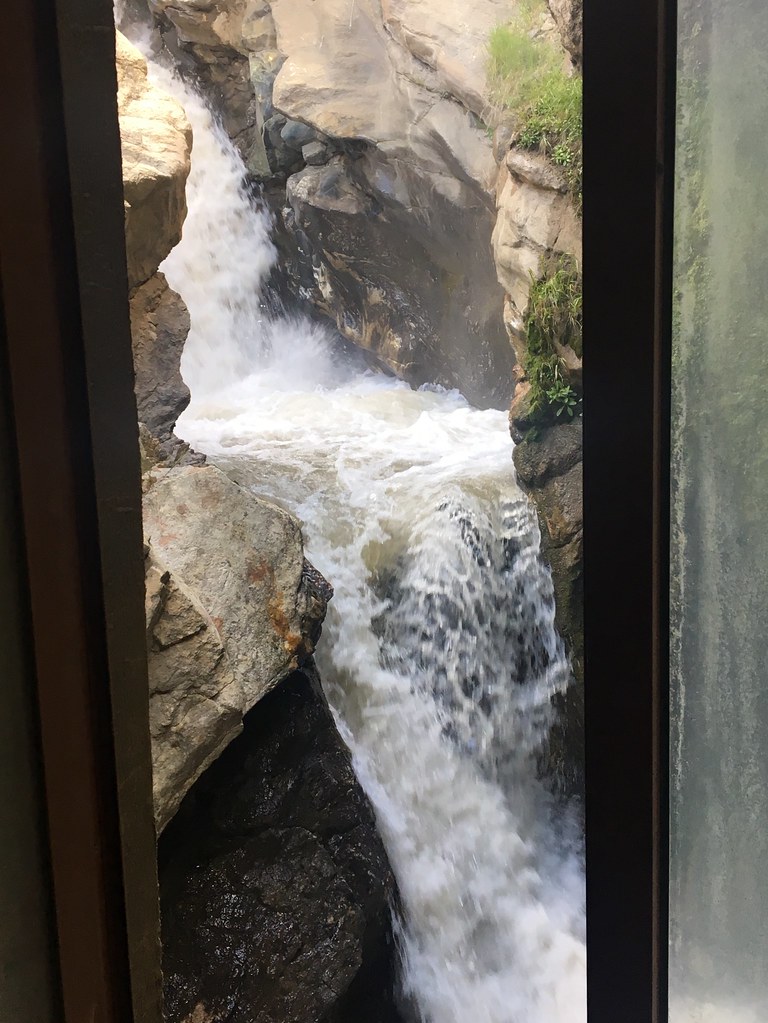

Our driver Jomart met us at Sheron Homestay in the morning, and we stocked up 5-liter containers of water at the bazaar and pulled out money from Orion Bank. (There’s nowhere else to pull out or exchange money until well after you cross into Kyrgyzstan, so calculate what you need beforehand.) After lunch in Ishkoshim, we made a pitstop at the

After lunch in Ishkoshim, we made a pitstop at the