I’m torn about how to feel that we had so little time in Belgrade… On the one hand, it’s an incredible place and I really enjoyed the 24 hours I spent there. On the other, I also felt a bit uncomfortable at times, having read about the government’s treatment of journalists and free press and – I guess this is a big factor – because we stumbled onto an ultranationalist rally welcoming the return of a soon-to-be-convicted war criminal to the capital.

If I had to describe Belgrade in one word, it would be gritty. Compared to tiny Sarajevo, Belgrade is huge, with a population of about 2 million. We took the advice of a pair of Aussies we met in the hostel in Sarajevo and took a walking tour of Belgrade. Our guide, Tea (short for Teadora, pronounced “Tay-uh”), was fantastic – she spoke perfect English and had so many fantastic stories about the city. She shared homemade rakija and pepper spread, too, which didn’t hurt. Our walk took us through Skadarlija, the bohemian quarter of town, “Silicon Valley,” where young men and women went to show off flashy cars and plastic surgery successes in the years following the wars and hyperinflation of the 1990s, and the Fortress, which was really a smattering of different styles of fortification and protection that had been added to and rebuilt many times over the many centuries since Belgrade was founded. Mom and I ended the afternoon at the Nikola Tesla museum, where we got to touch 100,000 (watts? volts? units.) of electricity and see Tesla’s final resting place. Fun fact: Tesla only spent one day of his life in Belgrade, but he loved the city very much and requested that his remains be moved there after his death. Also, Tesla apparently was a great fan of pigeons. Who knew?

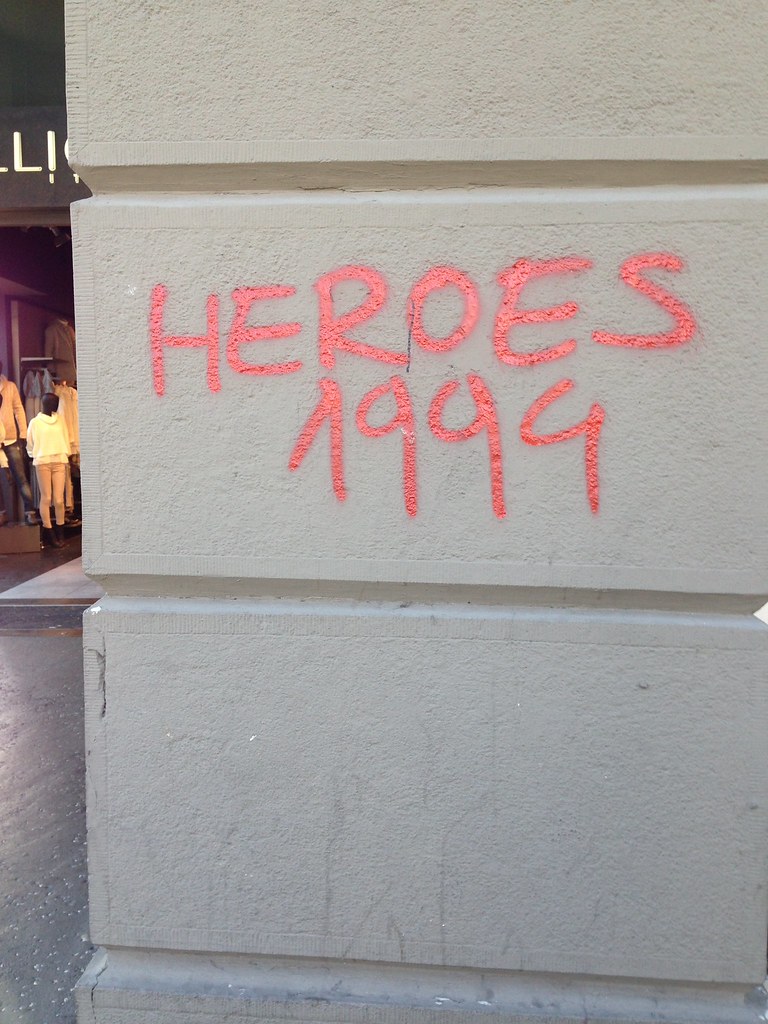

Obviously it was great to have Tea as a guide to the city, and I doubt we would have seen as much if we had tried to walk it on our own. The most valuable takeaway, though, was to get another perspective about the wars of the 1990s. Tea was just a kid when NATO countries bombed Belgrade in 1999, following Serbia’s actions in Kosovo. She recalled that at first, the bombings targeted strategic areas (like bridges and government buildings) and took place only at night – but with time, NATO realized this was not effective, and so started bombing civilian targets during the day and without warning. This had the intended effect of getting the Serbian government to cave, but also resulted in civilian deaths and destruction. Having spent several days in Bosnia, where we only heard of the horrors committed by Serbian paramilitary groups, it was an important alternate perspective to hear from a Serbian who was just a child at the time of the wars.

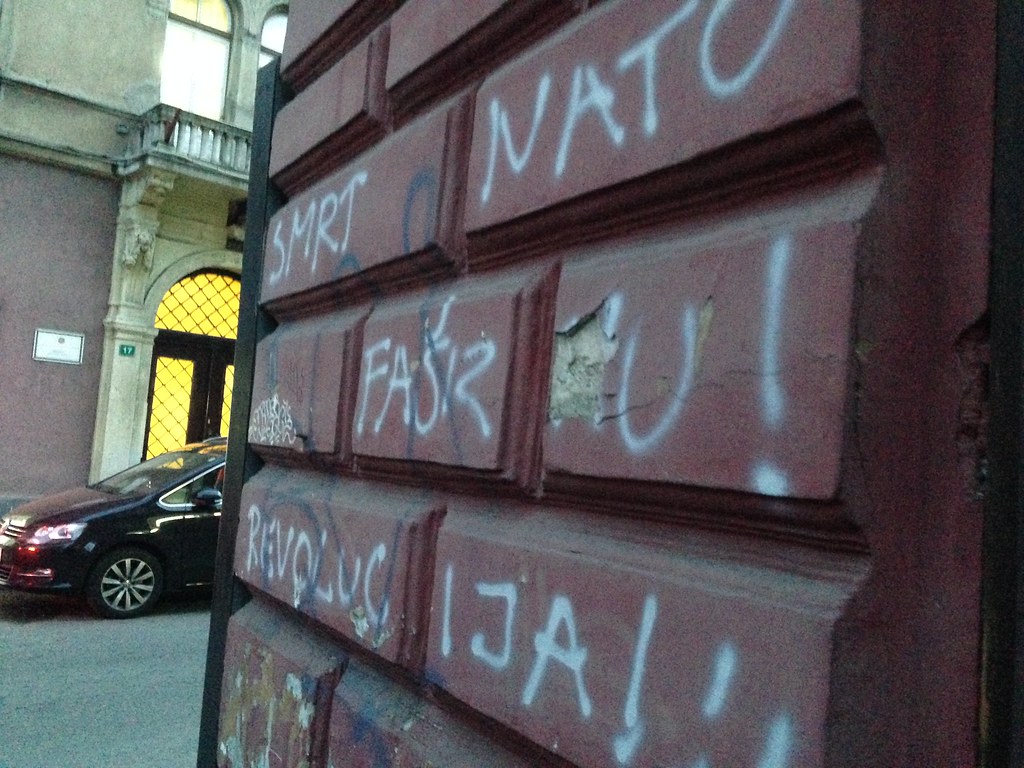

Whereas Zagreb had a very European vibe, Belgrade didn’t so much – this was not really a function of architecture (though the communist architecture from Tito’s time was much different than the decadent Austro-Hungarian style of Zagreb), but more because of graffiti and political posters. Much of the street art in Belgrade shared anti-EU and anti-NATO messages, and a lot of the posters at the nationalist rally had sprawled something about Russia or Putin on them. Although Serbia is a candidate country for EU membership, it continues to straddle East and West by maintaining close ties with Russia. It will be interesting as far-right parties continue to rise in the country whether Serbia will continue on a path to the EU, and if it does, what impact this will have on the European project.